Frames in GoLisp

by Dave Astels

I recently needed a more flexible and performant way of manipulating structured data, specifically data coming into the system in the form of JSON.

GoLisp has a way to convert back and forth between JSON and Lisp which uses lists for arrays and association lists for objects. This worked fine but association lists can be cumbersome to work with and relatively time consuming. To address this, I ported the frame system from my RubyLisp project, making some improvements while I was at it.

A frame is a collection of slots. A slot is a key-value pair. So

frames are structurally much like data structures such as Dictionaries

and Maps. In fact, the underlying implementation is a Go

map[string]*Data. What makes frames special is the functionality

that is built on top of that.

Background

The frame system is influenced by two languages that I have always held in high regard: Self [1] and NewtonScript [2]. Indeed, NewtonScript was heavily influenced by Self [3]. In a sense my frame system is a blend of NewtonScript’s syntax and Self’s lookup mechanism.

Self

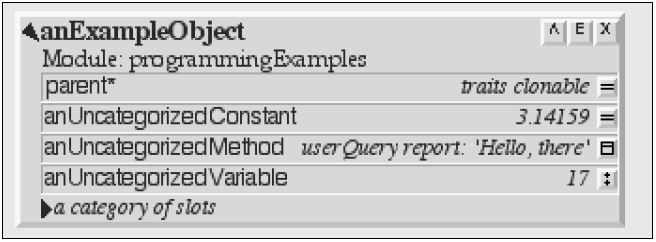

Self is a prototype-based dynamic object-oriented programming language, originally developed at Xerox PARC in 1986 and worked on at Stanford University and Sun Microsystems.

From the Self Handbook:

Objects are the fundamental entities in Self; every entity in a Self program is represented by one or more objects. Even control is handled by objects: blocks are Self closures used to implement user-defined control structures. An object is composed of a (possibly empty) set of slots and, optionally, code. A slot is a name-value pair; slots contain references to other objects. When a slot is found during a message lookup the object in the slot is evaluated.

NewtonScript

NewtonScript was the language developed by Apple for the Newton PDA.

y := {YMethod: func () print("Y method"),

yVar: 14};

x := {Demo: func () begin

self.newVar := 37;

print(newVar);

self.NewMethod := func () print("hello");

self:NewMethod();

self._parent := y;

print(yVar);

self:YMethod();

end};

Creating frames

NewtonScript is the most direct influence on my frame syntax. Rewriting the NewtonScript example results in:

(define y {y-method: (lambda ()

(write-line "Y Method"))

y-var: 14})

(define x {demo: (lambda ()

(set! new-var 37)

(write-line new-var)

(set! new-method (lambda () (write-line "hello")))

(new-method)

(set! parent* y)

(write-line y-var)

(y-method))})

Note how every slot name ends with a :. This is a special kind of symbol that

evaluates to itself. This allows it to be used without quoting, making

for a much cleaner syntax.

There are three ways to create a frame:

- using the literal notation shown in the above example, which surrounds a list of alternating slot names and values with a pair of curly braces,

- using the

make-framefunction, passing it the same list of names and values, and - cloning an existing frame.

The first two are functionally identical:

(define y {y-var: 42}) ==> {y-var: 42}

(define y (make-frame y-var 42)) ==> {y-var: 42}

In fact, the former is simply syntactic sugar for the latter.

The third way of making a frame is to clone an existing frame.

(define x (clone y)) ==> {y-var: 42}

This provides a couple of advantages:

- Cloning a frame containing default slot values and tweaking as required can greatly simplify code.

- Cloning allows a function to create new frames without knowing the actual structure.

A clone has a completely separate set of key-value mappings. Changing slot values in the clone has no effect on the original frame.

Manipulating slots

Frames support five basic slot operations:

- check for a slot’s existence,

- get a slot’s value,

- set a slot’s value,

- add a slot, and

- remove a slot.

The has-slot? function returns whether a slot exists in a frame.

(has-slot? y y-var:) ==> #t

(has-slot? y x-var:) ==> #f

The get-slot function retrieves the value of a slot.

(get-slot y y-var:) ==> 42

(get-slot y x-var:)

- Error in evaluation:

- Evaling (get-slot x y x-var:). get-slot requires an existing slot,

but was given x-var:.

If the specified slot isn’t found in the frame, an exception is raised. If

get-slot-or-nil is used instead, nil will be returned if the slot isn’t

found.

(get-slot-or-nil y y-var:) ==> 42

(get-slot-or-nil y x-var:) ==> ()

Changing and creating slots are both done using the set-slot! function:

(define y {y-var: 14}) ⇒ {y-var: 14}

; changing a slot

(set-slot! y y-var: 42) ⇒ 42

(get-slot y y-var:) ⇒ 42

; creating a slot

(set-slot! y new-var: "hello") ⇒ "hello"

(get-slot y new-var:) ⇒ "hello"

Removing a slot is done with the remove-slot! function.

y ⇒ {y-var: 14 new-var: "hello"}

(remove-slot! y y-var:) ⇒ #t

y ⇒ {new-var: "hello"}

The returned value is #t if a slot was removed, #f otherwise.

After playing around with the frame system a bit, I found using these functions to be somewhat cumbersome. To alleviate this I’ve added syntax shorthand inspired by Clojure’s map access.

There are shorthands for get, set, and has: (key: frame), (key:!

frame value), and (key:? frame key), respectively. Some of the

above examples become:

(y-var:? y) ==> #t

(x-var:? y) ==> #f

(y-var: y) ==> 42

(define y {y-var: 14}) ⇒ {y-var: 14}

(y-var:! y 42) ⇒ 42

(y-var: y) ==> 42

(new-var:! y "hello") ⇒ "hello"

(new-var: y) ⇒ "hello"

Parent slots

As the early example showed, frames can have slots that refer to other slots in a special way.

Self calls these slots parents and are designated by a trailing asterisk. An object can have any number of parents. GoLisp does the same.

NewtonScript calls them parents and prototypes, using slots named

_parent and _proto, respectively. Each frame can have a single

parent and/or a single prototype. When a slot is referenced, if it’s

not found, the prototype chain is searched. If it’s still not found,

the parent and its prototype chain is searched. This continues up the

parent chain. The following diagram illustrates this. The numbered

arrows indicate the order in which frames are searched.

Part of the rationale of supporting prototypes this way was to allow storing code and other static slot values in ROM, thereby reducing the use of more limited RAM.

While using a syntax very similar to NewtonScript, GoLisp uses a lookup algorithm very much like Self’s. Also like Self, GoLisp makes no differentiation between parent slots, and can have any number of them.

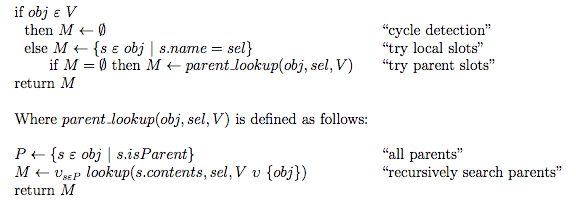

The function lookup(obj, sel, V) is defined as follows:

Input:

obj - the object being searched for matching slots

sel - the message selector

V - the set of objects already visited along this path

Output:

M - the set of matching slots

Algorithm:

Note: Parent slots are searched in arbitrary order.

> (define y {a: 1})

==> {a: 1}

> (define x {b: 2 p*: y})

==> {b: 2 p*: {...}}

> (p*:! y x)

==> {b: 2 p*: {...}}

> (a: x)

==> 1

This first looked in x, then y (via x’s parent slot).

> (get-slot-or-nil x c:)

==> ()

This first looked in x, then y (via x’s parent slot). Then y’s

parent slot is followed to x, but since x was already considered it

isn’t reconsidered and pursuit of this path is terminated.

The functions has-slot and get-slot use the above lookup to find

the slot in question. The set-slot! function is a bit different. It

doesn’t follow parent slots; if the frame passed to it has the slot

its value will be updated, otherwise the slot will be added. If some

frame in the frame’s parent graph has a slot of the same name, it

will be hidden by the new one.

Function slots

A slot can have any GoLisp data as its value. That includes functions. This provides the ability to do some object-oriented style programming.

(define shape {origin: {x: 0 y: 0}

extent: {x: 0 y: 0}

move-to: (lambda (x y)

(set! origin {x: x y: y}))})

(define rectangle {parent*: shape

area: (lambda ()

(let ((width (x: extent))

(height (y: extent)))

(* width height)))})

(define circle {parent*: shape

area: (lambda ()

(let ((r (/ (x: extent) 2)))

(* _PI_ r r)))})

> (define r {proto*: rectangle

extent: {x: 10 y: 10})

==> {proto*: {...} extent: {...}}

> (send r area:)

==> 100

> (define c {proto*: circle

extent: {x: 10 y: 10}})

==> {extent: {...} proto*: {...}}

> (send c area:)

==> 78.53975

There are a few things to note:

- a slot can have a lambda expression as its value

- within those lambdas, other slots in the same frame and its

parents can be referenced directly by using their names without

the trailing

:. E.g.(set! origin ...)and(x: extent). Note that this only works for slots in the frame that is the evaluation context. In the above example, whenarea:is evaluated for the framec, the search forextentbegins in thecframe even thoughareais defined in thecircleframe.

Within a functional slot value, symbols are found as follows:

- look in the immediately encompassing lexical environment (this

allows

letto override slots) - look in the frame (and its parents) that is attached to the current evaluation context

- look in the lexical environment of the frame

Implementation

This took minor changes to SymbolTableFrame. Here is the implementation of environment creation:

func NewSymbolTableFrameBelow(p *SymbolTableFrame) *SymbolTableFrame {

var f *FrameMap = nil

if p != nil {

f = p.Frame

}

return &SymbolTableFrame{Parent: p,

Bindings: make(map[string]*Binding),

Frame: f}

}

When a lambda is defined in a frame, this will ensure that any inner environments will have a reference to that frame to use for lookup:

func (self *SymbolTableFrame) ValueOf(symbol *Data) *Data {

localBinding, found := self.findBindingInLocalFrameFor(symbol)

if found {

return localBinding.Val

}

naked := StringValue(NakedSymbolFrom(symbol))

if self.HasFrame() && self.Frame.HasSlot(naked) {

return self.Frame.Get(naked)

}

binding, found := self.findBindingFor(symbol)

if found {

return binding.Val

} else {

return nil

}

}

func (self *SymbolTableFrame) SetTo(symbol *Data, value *Data)

(result *Data, err error) {

localBinding, found := self.findBindingInLocalFrameFor(symbol)

if found {

localBinding.Val = value

return value, nil

}

naked := StringValue(NakedSymbolFrom(symbol))

if self.HasFrame() && self.Frame.HasSlot(naked) {

self.Frame.Set(naked, value)

return value, nil

}

binding, found := self.findBindingFor(symbol)

if found {

binding.Val = value

return value, nil

}

return nil, errors.New(fmt.Sprintf("%s is undefined", StringValue(symbol)))

}

Sending a message to a frame (i.e. evaluating a function slot) creates

an evaluation context, connects the frame to it, and binds self to

the frame object:

frameEnv := NewSymbolTableFrameBelowWithFrame(env, f.Frame)

frameEnv.BindLocallyTo(SymbolWithName("self"), f)

return fun.Func.Apply(params, frameEnv)

This means that the above lookup rules will always work regardless of how that function slot got its value. For example:

> (f:! c (lambda () (write-line extent)))

==> <function: anonymous>

> (send c f:)

{x: 10 y: 10}

==> ()

Class based programming

The combination of parent and function slots being dynamically changeable can lead to some interesting programming approaches.

A prime example of this is the implimentation of a state machine. The functions for each state can be placed in different frames and transitions can modify the slot contaiing that state behavior.

Here’s an example of this.

(define state {name: ""

enter: (lambda ())

halt: (lambda ())

set-speed: (lambda (s))

halt: (lambda ())

transition-to: (lambda (s)

(set! state* s)

(enter))})

(define stop-state {name: "stop"

parent*: state

enter: (lambda ()

(set! speed 0)

(transition-to idle-state))})

(define idle-state {name: "idle"

parent*: state

set-speed: (lambda (s)

(set! speed s)

(transition-to start-state))})

(define start-state {name: "start"

parent*: state

halt: (lambda ()

(transition-tostop-state))

set-speed: (lambda (s)

(set! speed s)

(transition-to change-speed-state))})

(define change-speed-state {name: "change-speed"

parent*: state

halt: (lambda ()

(transition-to stop-state))

set-speed: (lambda (s)

(set! speed s))})

(define motor {speed: 0

state*: state

start: (lambda () (transition-to stop-state)) })

Now you can do things like the following:

(send motor start:)

motor ⇒ {speed: 0 state*: {name: "idle" ...}}

(send motor set-speed: 10)

motor ⇒ {speed: 10 state*: {name: "start" ...}}

(send motor set-speed: 20)

motor ⇒ {speed: 20 state*: {name: "change-speed" ...}}

(send motor set-speed: 15)

motor ⇒ {speed: 15 state*: {name: "change-speed" ...}}

(send motor halt:)

motor ⇒ {speed: 0 state*: {name: "idle" ...}}

Here’s another example, a simple stack based on the example in [4]:

(define Stack {

new: (lambda ()

{parent*: self

items: '()})

push: (lambda (item)

(set! items (cons item items))

self)

pop: (lambda ()

(let ((item (car items)))

(set! items (cdr items))

item))

empty?: (lambda ()

(nil? items)) })

> (define s (send Stack new:))

==> {parent*: {...} items: ()}

> (send s push: 1)

==> {parent*: {...} items: (1)}

> s

==> {parent*: {...} items: (1)}

> (send s push: 2)

==> {parent*: {...} items: (2 1)}

> (send s pop:)

==> 2

> s

==> {parent*: {...} items: (1)}

JSON

As I mentioned at the beginning of this post, processing JSON was an impetus for this project.

Here’s some example JSON:

{

"id": 1,

"name": "A green door",

"price": 12.50,

"tags": ["home", "green"]

}

This converts to the following Lisp:

{

id: 1

name: "A green door"

price: 12.50

tags: ("home" "green")

}

Note: the print output of frames simply dump the data structures and isn’t evaluatable. Specifically, lists are not quoted.

Conversion is obvious:

- atomic values (strings, numbers, etc.) are converted directly

- JSON arrays convert to/from lists

- JSON objects convert to/from frames

There is a pair of functions in Go for converting between JSON formatted strings and frames:

func JsonStringToLispWithFrames(jsonData string) (result *Data)

func LispWithFramesToJsonString(d *Data) (result string)

There are corresponding functions in Lisp: json->lisp

and lisp->json (strings are split across lines for formatting

purposes only):

> (json->lisp "{\"id\": 1,\"name\":\"A green door\",\"price\":12.50,

\"tags\":[\"home\", \"green\"] }")

==> {id: 1 name: "A green door" price: 12.5 tags: ("home" "green")}

> (lisp->json {id: 1 name: "A green door" price: 12.5 tags: '("home" "green")})

==> "{\"id\":1,\"name\":\"A green door\",\"price\":12.5,

\"tags\":[\"home\",\"green\"]}"

Conversation to JSON completely ignores function slots.

> (define shape {origin: {x: 0 y: 0}

extent: {x: 0 y: 0}

move-to: (lambda (x y)

(set! origin {x: x y: y}))})

==> {extent: {...} move-to: <function: anonymous> origin: {...}}

> (lisp->json shape)

==> "{\"extent\":{\"x\":0,\"y\":0},\"origin\":{\"x\":0,\"y\":0}}"

If you want to have functions in frames that are moving to/from JSON, put them in a separate frame and put a reference to it in the data frame after converting from JSON.

> (define shape-proto {move-to: (lambda (x y)

(set! origin {x: x y: y}))})

==> {move-to: <function: anonymous>}

> (define shape (json->lisp "{\"extent\":{\"x\":0,\"y\":0},

\"origin\":{\"x\":0,\"y\":0}}"))

==> {extent: {...} origin: {...}}

> (proto*:! shape shape-proto)

==> {move-to: <function: anonymous>}

> shape

==> {extent: {...} origin: {...} proto*: {...}}

In closing

If you need more efficient, flexible manipulation of structured data, frames can help. If you are moving data between GoLisp and JSON, frames can help. The syntax is minimal and clean, and the implementation is efficient in terms of both time and space.

References

[2] The NewtonScript Programming Language